On the way to Guatavita Lake, we drive along the damp stretch of road, bumping along as the path begins to ascend steeply towards the sky. We’re surrounded by a cotton candy haze of low-hanging clouds and fog.

“The weather is like this almost all year round,” our guide, Alejandro, says from the front seat of the car in soft tones that hum when he speaks.

We continue to bump along through a green patchwork of rolling hills that have engulfed us, some dotted by native flora, other patches cleared for agriculture and farming. Potato farms are particularly popular here, we learn.

We’ve been driving for over an hour to the northeast of Bogota until we arrive at the starting point for the short trek up to Guatavita Lake.

The constant drizzle curls my hair and drips from my eyelashes onto my cheeks before rolling down my face and onto my bright green plastic rain poncho.

The earth makes squelching noises under my feet, adding to the noise of light rain, soft wind and the sound of fellow visitors and school students laughing as they, too, put on their brightly-coloured ponchos.

“The indigenous people from this area were called the Muiscas,” Alejandro whispers as we begin our walk, the tone of his voice adding to the mystery and wonder of the place.

“The word ‘Muisca’ in their Chibcha language means ‘the people’ and this land, Cundinamarca, in Chibcha, means the land of the condors, which is Colombia’s national bird,” he continues.

The condor, which has a wingspan of around 10 feet and is one of the largest birds of prey in the world, is no longer found in these parts of Colombia, Alejandro says. They’ve moved to less inhabited areas in the south near the Amazon jungle.

Looking up to the surrounding mountains, you can imagine these birds soaring through the air, gliding powerfully through the sky before landing on their hapless prey, spotted from above.

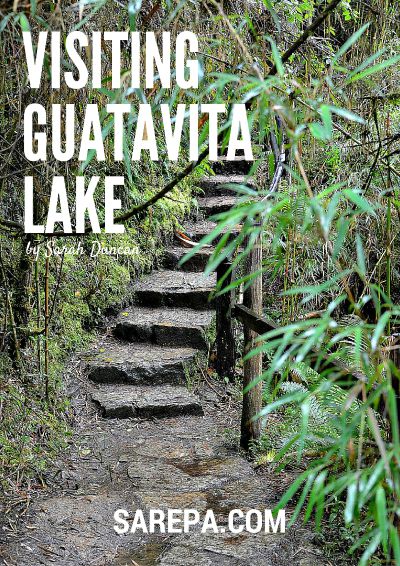

From the entrance point to Guatavita Lake it is about a 15 minute trek, but on this walk up the mildly inclined steps, we took a journey into a distant, magical past. Because Guatavita is more than just a lake, after all.

Far from the chaos of Bogota, we walk through the Paramo ecosystem, which some scientists believe to be evolutionary hotspots and hotbeds of biodiverse activity.

They’re mostly found in northern parts of South America including Colombia, Venezuela, Peru and Ecuador. But the ecosystem is largest in Colombia and through the Andes.

Walking through the Paramo we spotted Espeletia plants, also known as Frailejon, which are shrubs that only grow in these high altitude ecosystems. They have a thick trunks and large leaves which are covered in a soft fur that protects the plant from frost and the brisk temperatures in these parts.

The warm air, all the way from the Pacific, blows through these areas and cools before precipitating over the mountains, creating the almost all-year round fog that we noticed on the drive up.

These unbelievable little shrubs absorb water from the clouds, which is then past through to the roots and into the soil. These little guys grow just one or two centimetres per year. Just imagine how old this guy (on the right) is!

The local indigenous people of Colombia faced quite the ordeal once the Spanish arrived way back in 1499. Those who survived the introduction of disease were left with some pretty rough Spaniards to deal with, who wanted their vast fortunes of gold, among other things.

For the Muiscas, gold was valuable, sure, but not in the way that we might think. Gold was used in ceremonies, to denote social status, but it was also their material of choice when making handicrafts because the shiny material was so abundant. It was also used during ceremonies, too, right here at Guatavita.

This is the very spot where the story of El Dorado and its buried treasure originates, and it’s thanks to the local indigenous folk.

Way back in the day, before the Muiscas had to face the Spaniards, each of their regions had a leader, whom was called a Cacique. But not any ol’ Musica got the opportunity to become one of these revered folk, it took a long and arduous series of tests before he was given the coveted title.

The tests began when the chosen boy was just nine years old. He would be put in a room and denied the world’s earthly pleasures such as salt and spices.

Instead, he was only allowed to eat boiled vegetables and meat. After nine years eating like a paleo, before it was hip, at 18 years old, and at the peak of his sexual awakening, he was tested yet again. This time several beautiful women were to accompany him and be at his beck and call.

If he could deny these “cuchas”, which means “woman more beautiful than rainbows” and not the modern translation “old woman”, they could then proceed to the next test. If he couldn’t help but have his cake and eat it, too, then he would be cast out from the community.

If he passes this most difficult of tests for an 18-year-old, then he was given a house full of all the pleasures of the world. Yes, even salt and spices and beautiful cuchas.

Could he at last enjoy such pleasures? Of course not! He had to refrain from any of these things, but live under the same roof with them, just for one more day. If he could last a mere 24 hours more, then he could become a Cacique.

But, the ritual doesn’t end there, and this is where the story of Guatavita Lake really comes alive. These Caciques would arrive at the lake to make offerings in order to receive abundance from their goddess.

And how do they make such an offering? Well, they smother themselves with sticky stuff, probably honey, which is rubbed into their naked bodies and then covered in gold.

They’d then walk up to the lake and, from a raft, throw pieces of gold into the water as an offering, an act which has since inspired curiosity and greed from treasure hunters from around the world.

Over many years Guatavita Lake has been drained, people have scuba dived to its depths and a channel was even dug up, leaving a V-shaped hole in the mountain. One hopeful man even suggested that more than one billion sterling worth of goodies were still sitting on the bottom of the lake.

Thankfully, the lake and some of the surrounding area is now protected and people are no longer able to come here to look for buried treasure or clean their cars (as Alejandro mentioned wasn’t all that uncommon not that long ago!) and, more seriously, it is no longer at risk of being further damaged in the pursuit of riches.

Walking up the steps to Guatavita Lake, I became short of breath because of the high altitude and thin air (we were 3,100 metres above sea level), but what really took my breath away was the energy, the history and the mysticism of this truly important and beautiful place.

Sarepa was invited to visit Guatavita Lake by Colombia4u and Destino Bogota on the Zipaquira Salt Cathedral and Guatavita Lake Tour. For more information about the tour, be sure to click here. All opinions are her own.

Pin this post for later!