Travelling through Colombia with my Iranian partner, the conversation always comes back to politics. Pej talks politics in his sleep, so there were no surprises when he began asking taxi drivers, waiters, friends and strangers what they really thought about the government, the president and the controversial Colombia peace talks with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in Havana, Cuba.

To say that the views from local Colombians were polarising would be an understatement. Some people said the peace talks were an inevitability because without it there was no hope for the country to move forward. Others said that the country had transitioned into a particularly dark period and that people were again afraid for their safety and security against the guerrillas, because they had not been controlled and contained by the current government.

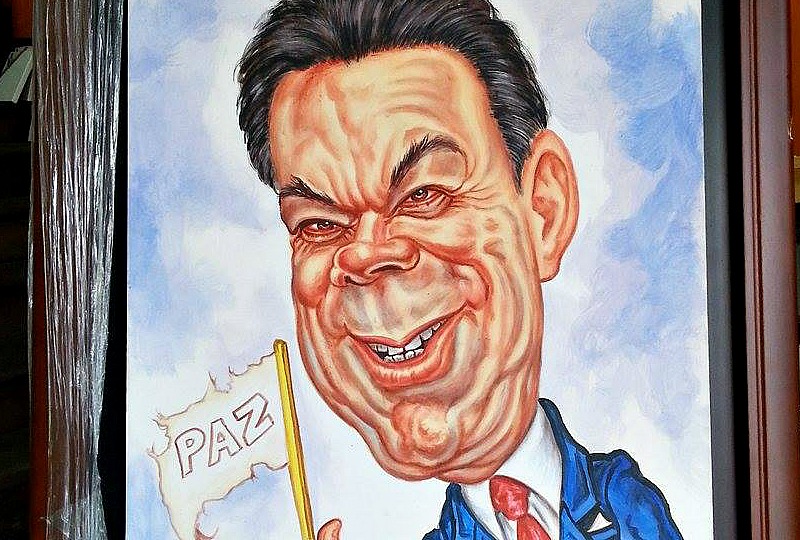

People from Medellin, where the previous president, Alvaro Uribe, is from, said that the current Colombian president, Juan Manuel Santos, was more interested in winning a Nobel Peace Prize than truly bringing stability to the country, wondering why the government would even make negotiations with a terrorist group.

People from the capital, Bogota, on the other hand, said that their only choice was to undergo a peace talks process, because there was no hope for the country otherwise. Going around killing the guerrillas wasn’t an option, either, because, at the end of the day, “they are Colombians, too.”

“Peace is possible!” one friend shares on Facebook, following the release of new information after a meeting between President Santos and FARC’s maximum commander, Rodrigo Londoño, in Cuba. Following the two-year long negotiations between the Colombian Government and FARC, they have reportedly made a “breakthrough”.

As part of this anticipated deal FARC will face transitional justice for crimes including kidnapping, murder and torture.

That transitional justice means that:

- Guerrillas can avoid going to jail if they come forward and admit their crimes

- Guerrillas who confess their crimes immediately will face confinement of between five and eight years, but no jail time

- Those who decide to confess once a trial has began can have their jail time reduced

- Those who are convicted but fail to confess, face up to 20 years in prison

- And those who are convicted of political crimes, including belonging to the FARC, will be eligible for amnesty and pardons

Currently there are more than 6 million people internally displaced within Colombia, the second highest number in the world, only trumped by Syria, according to the UN. The half-century armed conflict is reportedly the biggest contributor to this sad statistic.

But displacement isn’t the half of it, decades of conflicts has reportedly left a damaging mark on the collective consciousness of Colombians, leaving them with a broken self-esteem after facing the psychological effects of years of war and violence. At least 10 percent of adults in Colombia reportedly suffer from psychological trauma, including depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

No doubt Colombians are hungry for peace. A walk through Colombia’s capital is testament to that.

The guerrillas are ready for peace, too. They’re no longer a faceless mob who have retreated into the jungles. They have stories, too. Edifrando Valderrama Holguin was recruited to Las FARC at just 12 years old. “In the mountains, if I saw someone who was not part of our group, I had to kill him,” he told Quartz. “If I had questioned the ideology of the FARC, they would have called me an infiltrator and killed me.” Kill or be killed.

Now, thanks to the input of local organisations, Valderrama wants to be a yoga teacher and he’s not the only one being reformed. Close to 57,000 former rebels have been demobilised and around 30,000 of them are enrolled in reintegration programs that offer education and psychological services.

The peace talks, the civil war, the Colombian government – this is obviously a situation that is incredibly complex, more complex than I’ll ever understand, but yes, hopefully peace really is possible.

As Santos said during his recent meeting in Cuba, “not everyone in the world will be content, but I’m sure in the long run we’ll be much better off.”

Let’s hope so.

What do you think about the peace talks in Colombia? Share your thoughts and opinions in the comment section below.

Sign up to receive your 15-day Inspire Guide to Colombia

[mc4wp_form]

Hey, only just came across your blog, as I saw it advertised on your facebook profile. Great article! I have been following the peace talks for a while now, and for the first time I have hope that a lasting agreement can be achieved, as it is always the civilians that suffer most. Colombia is such a beautiful country and the Colombians I met so far, were so full of love. They really deserve to put this all behind them, find out what happened to their disappeared relatives, receive psycho-social support, and start a nice peaceful chapter of their life.